History

Early Settlers

Glenville Village 1870 to 1904

Glenville was established on November 6, 1872, and became incorporated as a village on October 4, 1870, by a vote of thirty-nine for and ten opposed. The area included what is today the western end of Bratenahl between Doan Creek and Nine Mile Brook.

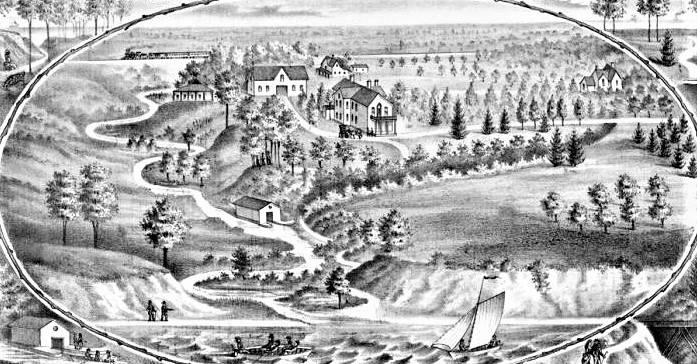

Shady valleys bisected by streams gave the area its picturesque name. New England farmers were the first to settle, followed by immigrants from Scotland, Ireland, and England. Truck farms operated by Germans hauled their produce to the city and returned with loads of manure from the Central Market horse barns.

William J. Gordon was the first mayor. With a population of 500, Glenville had three stores, three hotels, one blacksmith shop, one shoe shop, and one carriage shop.

The Burton & Moses allotment, a 62-lot development, was entered at the Cuyahoga County Recorder’s Office in October 1871. Dr. Erasmus Burton and Charles Moses developed the area. Burton graduated in the mid-1840s with a medical degree from the newly formed Cleveland Medical College, a Western Reserve College department in Hudson, Ohio. He was one of three generations of Burtons practicing medicine for ninety-two years.

In 1885, German-born Christian and Louisa Gottschalt bought the first of 12 lots they would eventually own in the Burton & Moses Allotment.

The Adams & Burton Subdivision, a 45-lot development on Foster Avenue, was entered at the Cuyahoga County Recorder’s Office in 1889. Darius Adams, an early settler who was a successful contractor and real estate investment partner with Dr. Erasmus Burton, developed the area.

Dr. Levi Haldeman purchased 30 acres north of Lakeshore Boulevard from Mary Bratenahl.

A 22-lot Haldeman re-subdivision was entered at the Cuyahoga County Recorder’s Office in 1891. Haldeman owned practically all of the lakefront property east of Burton Avenue to Clark Avenue (East 105tth Street). The allotment was platted for Clevelanders to build summer retreats on small lots on either Haldeman Roadside.

The Adams Foster allotment was developed in 1896 with 43 lots on both sides of Foster Avenue parallel to the Burton Moses allotment.

A 17-lot development known as the Haldeman & Patton Allotment on the south side of Lake Shore Boulevard west of Doan Street was entered at the Cuyahoga County Recorder’s Office 1903. Dwight D. Haldeman, Frank M. Haldeman, and James Patton developed this area. To maximize sales of land in his allotment, Patton laid out Birchton Road (Brighton Avenue).

Glenville continued to grow into a middle and upper-middle-class residential community abutting Cleveland to the east and running from Superior Avenue north to the lake. It was crossed from west to east by the Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad, which served as a commuting line for the northern Glenville residents, especially those living in the section known as Glenville on the Lake. Those living in the southern part of Glenville, most of whom lived there year-round, were already served by the Lake View & Collamer Dummy railroad's interurban cars.

The Lake Shore Railway merged with the Michigan Southern and Northern Indiana Railroad in 1869 to form the Lake Shore and Michigan Southern Railway, giving one company the whole route from Buffalo to Chicago. The first locomotive traveled the entire length of 1,013 miles. The main track passed through Glenville.

The wealthy started to plan to build elegant summer residences among the glens on the lake's shore. Private railway cars were used by the very rich to bring their needs for their summer homes.

The Village of Glenville on the Lake included about three square miles of territory, but only a part became built up. The Lake Shore & Michigan Southern Railroad built the Coit Station in 1871 with a siding for passengers east of Eddy Road north of the tracks. The railroad also built the Glenville station west of Doan Street (East 105th Street) on the tracks' north side. The line made it possible for those residents already living out on the lakeshore year-round to continue to maintain employment in the city.

By 1900, the population of Glenville was over 5,000. The next year, Glenville witnessed scandals in both its municipal government related to gambling and its school board regarding the misappropriation of coal. Many of its citizens were upset, and the idea of a merger with prestigious Cleveland, with the increased services available, began to seem very attractive to many.

Glenville's annexation to the City of Cleveland was defeated in 1902 by a vote of 716 to 467. Though Glenville voted against annexation, the second ward at the south end of the village voted for annexation. The ordinance authorizing annexation of Ward 2 to the City of Cleveland was passed in March, with the County Commissioners granting annexation in November.

Glenville’s anti-gambling forces had found a powerful ally in Frederick Goff. He was awakened late one night by a crowd of earnest citizens who demanded that he consent to become a mayoral candidate on a platform of suppressing racetrack gambling.

Goff rejected the plea, perhaps from a lack of experience or friendship with the track’s members. Despite his reluctance, the leaders of the crowd told him it was his duty. He consented just in time to become a nominee.

Goff ran for mayor on the Republican ticket and won in a special election in April 1903 despite his protests. Acting as mayor, he succeeded in abolishing gambling at the Glenville Race Track, much to influential friends' dismay. This was Goff's introduction into public affairs of a community that soon came to know and appreciate his inflexible adherence to the law, order, and duty.

In his first run for office, Abram Garfield became a councilman by a vote of 413 for and 281 opposed. Garfield introduced an ordinance that provided for the Village of Glenville to be classified as a city. Clifford Neff ran for the Republican nomination for the solicitor of Glenville.

Mayor Goff, and C. A. Judson, president of the school board, were presented with petitions from all of the community’s wards south of the railroad tracks requesting a merger with Cleveland.

Both Goff and Judson were attorneys, and neither was associated with the scandals. They became the principal implementers of the merger negotiations. The one difficulty was Glenville on the Lake’s disaffection with a merger. Many of the summer residents who lived on Euclid Avenue were aware of how rapidly large cities changed, particularly with escalating property valuations and taxes coupled with almost no land-use control. They had moved to Glenville on the Lake to escape Cleveland’s filth, noise, crime, government, and teeming immigrant masses. Hostility toward Tom Johnson’s Progressive policies and contentious personality was a motivating factor in avoiding annexation at all costs.

Secession leaders in Glenville on the Lake allowed public debate over the wisdom of annexation to run its course while maneuvering behind the scenes.

First, the secessionists had to determine whether their small number of taxpayers would be willing to go it alone.

Second, leverage on the Glenville council had to be regained. The May 1903 at-large election had eliminated Glenville on the Lakes’ assured seat. That November, Albert S. Ingalls was appointed to fill a vacant council seat.

Frederick Goff enlisted the aid of Liberty Holden to help resolve the conflict between the two sections of the community. Holden agreed to lead the drive to have Glenville on the Lake become a separate municipality.

Third, the legality had to be established. In early 1905, Ohio House Bill 271 was signed into law, which eliminated the size restriction for creating a township.

The principal problem to be addressed was to settle on some agreed method of structuring the new community to prevent the intrusion of unwanted types of land use. Although recent residents of Marble & Shattuck Chair Company and Lucas Machine-Tool Company were quiet and didn’t seem to disturb the village too much, the founders did not want any more businesses moving into the area.

One of the few models available to Holden was Tuxedo Park, a restricted community in New York founded by Pierre Lorillard. The difference being that Lorillard had begun with title to eleven thousand acres of land and could determine the usage unilaterally. Holden was advised to do something similar, even though it could only be done by each resident individually.

Holden, along with Goff, Charles Britton, Arthur Baldwin, and Abram Garfield, thrashed around for a solution. They also received pressure from Collinwood residents Samuel Mather and Charles Bingham. Eventually, Judge Louis Grossman, John D. Rockefeller’s attorney, offered a resolution.

The solution had deeds to every property in Glenville on the Lake to be revised to restrict land use to single-family homes for fifty years. This simple solution required an astonishing leap of faith from the property owners.

Over a year, Holden and Goff visited every property owner from Gordon Park to Coit Road to request that they convey the deeds to their homes to Guardian Savings and Trust Company as trustee. The owners were returned deeds with provisions limiting the property's use to residences for a term of fifty years. After more than a year’s work, the two men persuaded more than 150 of the neighbors to participate, demonstrating the trust and the high regard for the two men.

The re-granted ownership forbade the construction of railroads, businesses, manufacturing enterprises, or any structure that would emit offensive odors, noise, or smoke. Nor could they erect apartment houses or establish resorts, hotels, saloons, stables, or even picnic grounds. The Country Club, James Patton’s fruit farm, and the Schmitt-Gamble greenhouses and the two manufacturing plants were grandfathered from having such restrictions. The provisions of not selling wine or malt or spirituous liquors of any kind were aimed at keeping Glenville’s working classes at bay.

By the summer of 1904, the Fourth Ward (Glenville on the Lake) was ready to roll out its escape plan. The necessary petition was drafted and circulated, signed by Howard M. Hanna Jr., Robert L. Ireland, L. Dean Holden, Albert S. Ingalls, and Liberty E. Holden.

Those wanting to annex to Cleveland organized a new offensive. In July 1904, a petition presented to the council requested Glenville’s annexation be placed on the ballot at the next regular election.

In August 1904, the Glenville council announced that it had received petitions signed by 88 Fourth Ward property owners seeking approval of the detachment of the Fourth Ward, the first step in the process of incorporating the Fourth Ward into a township. The Plain Dealer reported, “Never before was such interest shown in council’s proceedings.”

There was strong objection to the southerly limits be immediately south of the railroad tracks. Recognizing that Glenville would never accept the loss or the railroad revenues, a new ordinance was drafted, setting the southern boundary north of the railroad tracks.

There were further objections, with the primary being the loss of tax receipts. The Fourth Ward accounted for ½ to ¾ or Glenville’s operating revenue.

At a September 19, 1904 council meeting, one of the yea voters supporting the secession, Councilman Sprengel, failed to attend the council meeting. The vice mayor broke a 3-to-3 tie vote by voting no. The missing council member explained away his absence by saying it had been because of his mother’s sudden illness. At a September 26, 1904 council meeting, Sprengel asked for the opportunity to vote. There were no objections. In a surprise move, he cast his vote against secession.

On October 3, 1904, villagers jammed council chambers and spilled out in the hallways. Crowds on the sidewalk peered through every window. A group of anti-secessionists had come with a bucket of tar and a bag of feathers. The mayor hired extra law enforcement.

Councilman Sprengel again asked for a reconsideration of the vote against secession. The motion to reconsider was put forward, and four of the seven council members voted in favor of secession. The vote occurred shortly before midnight. Three hours of angry debate followed until the crowd silently filed out.

The anti-secessionists made good on a promise to fight on. Glenville’s solicitor asked Cuyahoga County’s Common Pleas Court for an injunction prohibiting the secession. The court issued a temporary restraining order but ultimately ruled in favor of the withdrawal. In so doing, the court ruling recognized Ward Four’s legal standing as a separate entity.

At the end of October, Mayor Goff, Councilman Ingalls, and two others resigned from their Fourth Ward positions.

On October 15, 1904, the Cuyahoga County Commissioners approved the “erection” of Bratenahl Township. The name, Bratenahl, was taken from Bratenahl Avenue (later East 88th Street), which ran north from St. Clair to the Charles Bratenahl family home. Bratenahl Avenue was one of the entrances into the village and marked Cleveland’s northeastern boundary.

Had Bratenahl remained a township, an incorporated community could have been annexed without the township’s consent. On November 19, 1904, the appointed trustees of Bratenahl Township, Liberty Holden, Robert Ireland, and James Patton, ordered a special election to be held on November 21, 1904. All 68 voted in favor of establishing a village. On November 28, 1904, Clerk Clifford Neff reported to the trustees that the Village of Bratenahl had come into being.