Places

Homes Current

12407 Lake Shore Boulevard "Gwinn"

Plat No. 631-08-003

Sublots 36 and 37 in the Golbert, Coe and Shipherd Subdivision

Gwinn is listed in the National Register of Historic Places

Willam Mather wanted to live near his half-brother, Samuel Mather. During 1905 and 1906, he considered buying three separate parcels west of Doan Street (East 105th Street). But Mather and his widely-admired landscape architect, Warren Manning, favored the Gilbert, Coe, and Shipherd Subdivision subplots 36 and 37. The sites had many unique attributes. The land sat on a bluff with a shoreline forming a natural amphitheater that could become an an asymmetrical, well-balanced house and grounds plan. An uninterrupted lake view and a dominant bluff-top house site flanked by a great group of trees gave dignity and aspect to a home that none of the other lots offered.

Charles and Portia Heear acquired subplot 36 from David and Ellen Howley and subplot 37 from Jeremiah and Mary Hogan on May 9, 1909.

The Heers sold both lots to William Mather on the same date. Title transfers also show Minerva Shipherd selling subplot 37 directly to William Mather. Charles Bingham sold a small tract of land between subplots 37 and 38 to William Mather on July 14, 1908.

Mr. Mather would only consider the purchase with the abandonment Shipherd and Beach Avenues on either side. Council voted to vacate both streets on June 8, 1908. Mather began work on Gwinn immediately following the vacating of the two avenues.

To protect the outlook from his home, Mather acquired subplot 30 from Clarence and Julia Leavenworth on June 4, 1907, subplot 32 from Mary Wain on June 3, 1909, and subplot 28 from Cleveland Trust on November 28, 1910, all on the south side of Lake Shore Boulevard to be used for fields, gardens, and practical use.

William Mather, a fifty-year-old bachelor, undertook the building of a lakefront estate for himself and his half-sister, Katherine. He consulted with Warren Manning as to a suitable architect. Manning suggested Charles A. Platt, a New York architect called the “best country-house designer of the post-1900 period.”

Charles Adams Platt was born in 1861 in Manhattan. He explored his ideas on villa architecture during an 1892 trip to photograph Renaissance gardens in Italy. After returning from Italy, Platt received house and garden commissions for entire country estates. Platt continued to design country houses throughout his career, but he devoted much of his time to important urban and institutional commissions after 1920. Many of these commissions came from the Vincent Astor estate office, which employed Platt from 1906 through 1932, and also from residential clients with institutional interests.

anning’s surprise, Platt accepted Mather's project on the condition that he would have control over landscaping the grounds, which he considered an integral part of his architecture. Mather agreed and consoled the disappointed Manning with the limited role as advisor on plantings. Mather and Platt formed a solid friendship. Mather proved to be as discerning as his architect in finding elegant design solutions to architectural and landscaping issues while avoiding unnecessary extravagance.

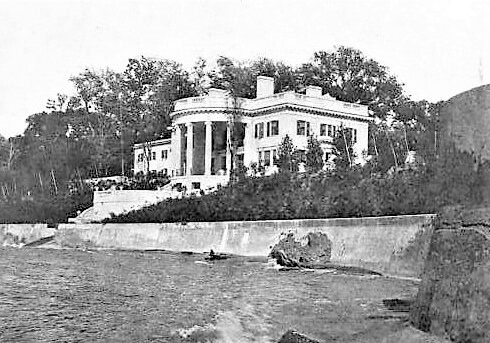

Gwinn, named for William Mather’s mother, Elizabeth Gwinn, was a sixteen-room Italian Renaissance villa. Charles Platt subscribed to the classical aesthetic concept with the design of a restrained exterior. He modeled Gwinn’s north porch after the White House, with the most prominent architectural feature being the majestic semicircular portico facing Lake Erie, with its paired curving stairs and fountain court.

The main entrance was on the west end of the home was unusual in that the main entrance on other Bratenahl lakefront homes faced the street. The rooftop balustrade effectively hid the shallow roof. Platt concentrated ornamental detail in a few spots, such as the Tuscan doorway.

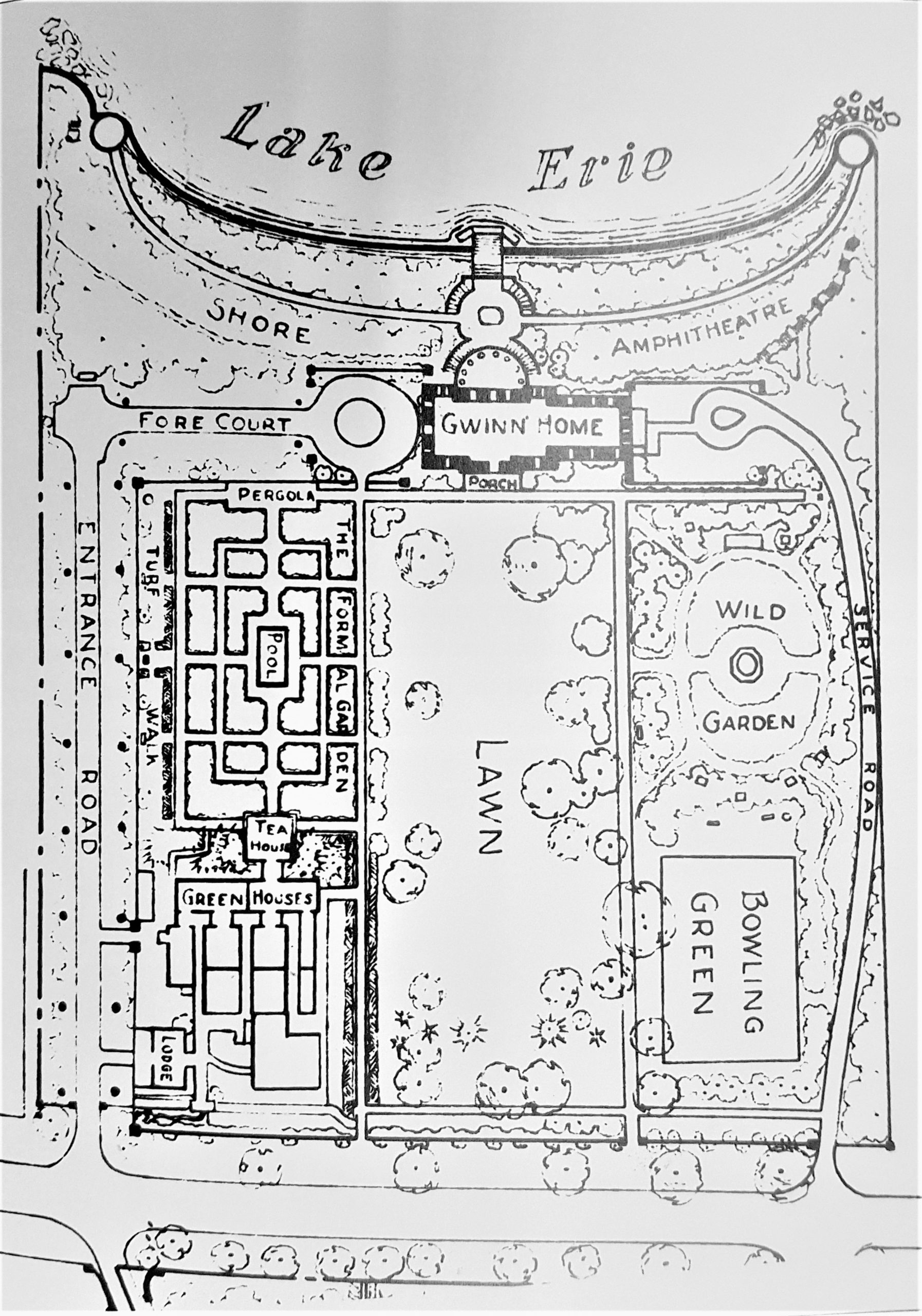

Gwinn was perhaps more significant for the planning of the five-acre site, with its lake frontage on the north and garden to the south. Much thought was given to gracious outdoor living when planning the estate. A Renaissance balcony overlooked Lake Erie and the geometric Italian gardens by the lake. Its formal gardens laid out in the west section of the property.

The construction of an asymmetrical concrete breakwater changed the rugged water's edge into a formal setting. A terraced series of stairs descended to the beach from the house twenty-eight feet above the level of the lake. On the terrace landing, there was a fountain with a sculpture in the Italian Mannerist style. The majesty of the lake façade counterbalanced the more human scale formal and symmetrical garden.

Formal gardens were developed south of the house to Lake Shore Boulevard. A pergola and reflecting pool with a fountain in the center and a teahouse with colorful hand-painted ceilings and walls flanked the gardesn to the west.

The center section had a vast expanse of lawn extending south from the terrace. East of the lawn had a wild garden to the north that was Manning's expression of aesthetics. A bowling green occupied the area south of the wild garden.

A high wall enclosed the five-acre retreat. The entrance drive ran along the western edge of the property, leaving the garden frontage open to Lake Shore Boulevard. The design and layout of this house and grounds, both in decorative detail and in the overall plan, reflected an attempt to approximate the effect of a sixteenth-century Italian palace.

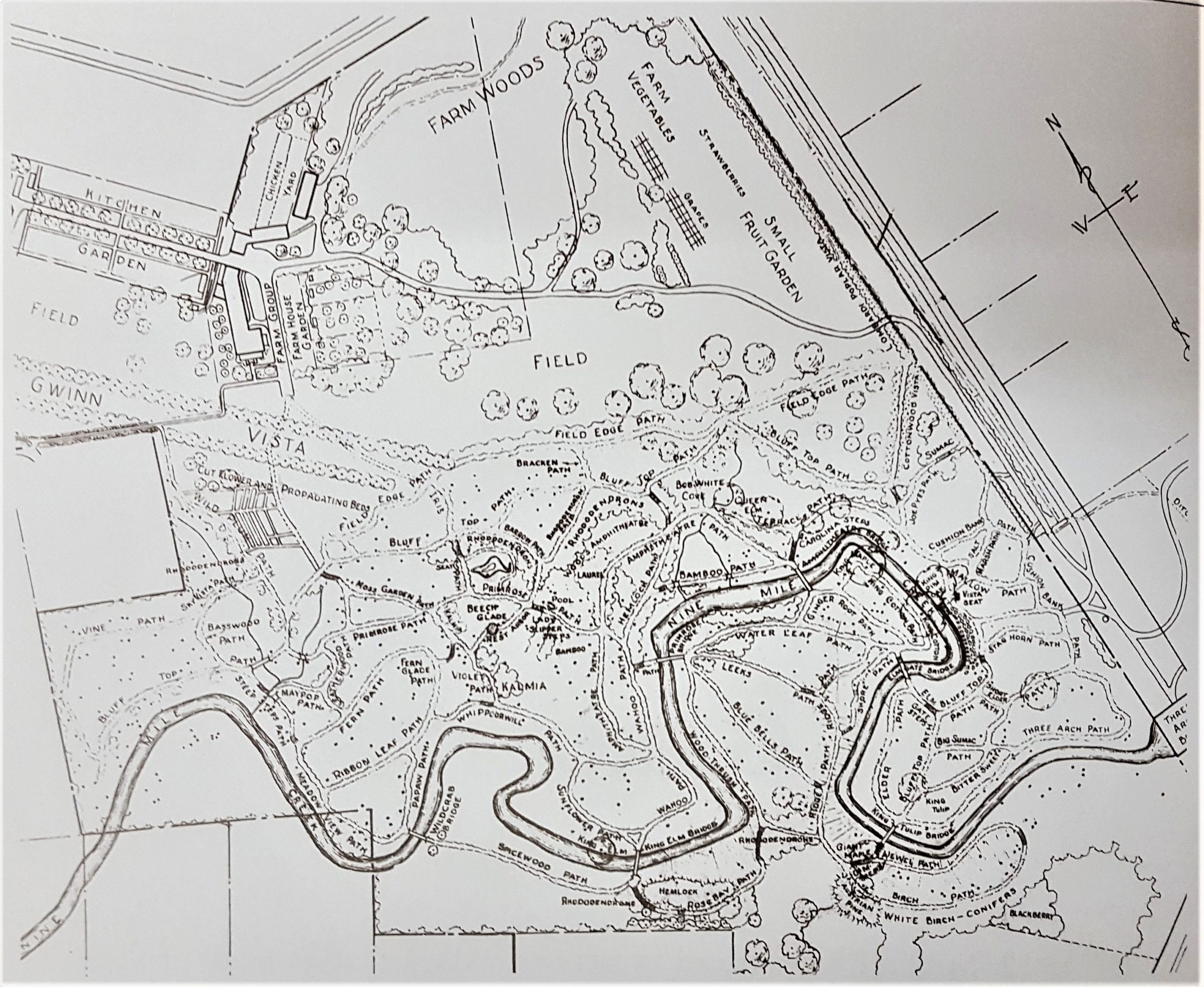

The property south of Lake Shore Boulevard was given to Warren Manning to plant with his naturalistic style as a setting for horseback rides and quiet contemplation. It also housed the servant quarters and stables.

Remarkably, each man was stimulated by the opposing views of the other to masterfully express both concepts in a combined harmony overseen by their astute client. Mather’s appreciation for natural and man-made beauty was recognizable by the world-side search for plantings, sculptures, and architectural inspiration.

James D. Ireland Jr. inherited the estate on September 9, 1959, from his mother, Elizabeth. Elizabeth hoped that James and his family would live there. She had also contemplated the idea of using the estate as a conference center.

James and Cornelia Ireland decided to turn the property into a civic center. They succeeded in accomplishing by selling the property to the Elizabeth Ring Mather and William Gwinn Mather Fund, a non-profit corporation. With the cooperation of University Circle Inc., an organization that Mrs. Mather helped to inspire, Gwinn was made available for civic groups and out of town dignitaries to use for meetings, luncheons, and dinners. The house continued to be maintained with its original art treasures and English antique furniture.

In a separate report to the council, Carl Feiss passionately defended Gwinn’s use as a conference center. He viewed the zoning non-compliance as the only way to preserve “one of the few great houses on the shore of Bratenahl, which has served the village as an anchor against the heavy tides of deterioration and obsolescence.”

The Cleveland Orchestra expressed an interest in Gwinn property on the south side of Lake Shore Boulevard as a possible summer home. Orchestra officials walked the site and discovered that the noise from the freeway was too much and withdrew consideration.

Terwyn Properties LLC acquired the estate on October 12, 2007.