History

Tragic Happenings

Thomas Hoyt Jones Jr. - A Murder on Kelley's Island

Around 7 p.m. on Monday, November 5, 1984, the phone rang at the Kelley’s Island Police Station. Located in Lake Erie's western basin about four miles north of the Ohio mainland at the Marblehead peninsula, Kelley’s Island is home to about 150 residents year-round and about 1,500 residents during the summer. The island is dotted with homes, summer cottages, and a few restaurants and bars that cater to a large contingent of summer visitors, many of whom visit the state park and campground on the island. Access to the island is limited to boat or airplane.

As a result of the phone call, Kelley’s Island Police Chief Charles Moore learned that employees at a Cleveland business owned by Thomas Hoyt Jones, Jr. were concerned because they could not reach their employer. Jones should have returned to his home at Bratenahl Place from a visit to his cottage on Kelley’s Island and should have been at work that Monday. He didn’t show up or contact his office.

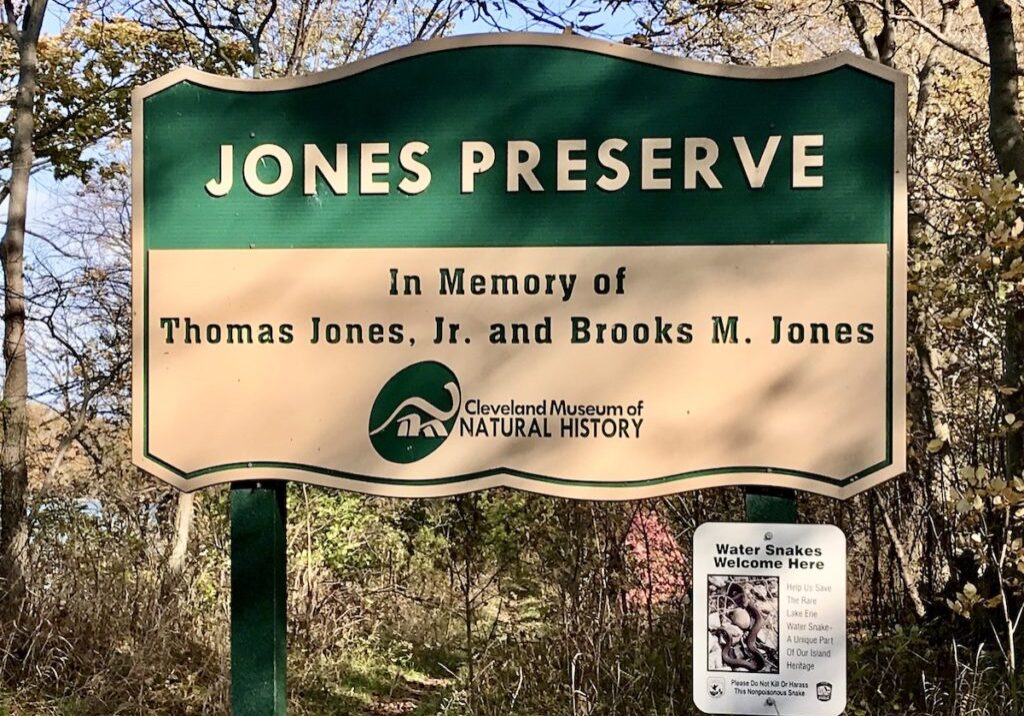

Police Chief Moore was familiar with the Jones family. Thomas Hoyt Jones, Sr. had purchased 50 to 60 acres of land on the northeast point of Kelley’s Island in 1940, and the family had been regular visitors to the island through the years. Recently, Thomas Jr. and his brother Brooks Jones had donated about 21 acres of the family’s island land to the Cleveland Museum of Natural History to be used as a bird sanctuary.

Jones was a member of a prominent Cleveland family. His grandfather, Thomas A. Jones, served on the Ohio Supreme Court. His father, Thomas Hoyt Jones, Sr., made a name early in life as an all-Ohio quarterback at Ohio State University. A distinguished lawyer, Thomas Sr. had many notable clients, including Cleveland financier Cyrus S. Eaton and the Shaker Heights developers O.P and M.J Van Sweringen. In 1939, he became senior partner of the newly merged law firm Jones, Day, Cockley & Reavis. Today, the law firm has more than 40 offices worldwide, is known simply as Jones Day, and continues to carry Thomas Sr.’s name.

Thomas Hoyt Jones Sr. had two sons. Brooks Jones followed his father's lead, becoming first a lawyer, then a partner at Jones Day. Thomas Hoyt Jones, Jr. was repeatedly described in the newspapers at the time as a “millionaire Bratenahl financier.” He founded T.H. Jones & Co., a bond investment business in the 1940s, and Scurry-Rainbow Oil Ltd. in Calgary, Alberta, in 1950. He headed a syndicate that owned and developed large parcels of Canadian land. He married Virginia Hosferd “Hossie” Van Dozer in 1954, and they had two children. The couple divorced in 1982, and Hossie Jones died suddenly in her sleep in a Munich hotel in May 1984, only five months before the phone call to the Kelley’s Island Police Department.

Members of the Jones family lived at various times in Bratenahl. Jones’ parents, Thomas and Katharine Brooks Jones lived at 304 Corning Drive in the late 1940s. They lived on Corning Drive at the time of Thomas Sr.’s death from a heart attack on April 14, 1948. Katharine Jones traveled extensively after her husband’s death. Late in life, Katharine returned to Bratenahl, living at Bratenahl Place. She regularly traveled between Bratenahl and an apartment in Delray Beach, Florida. She died in Florida in 1979. Following his mother’s death and his divorce, Thomas Jr. divided his time between his residence at Bratenahl Place and the cottage on Kelley’s Island.

Chief Moore arrived at the Jones cottage at about 7:20 p.m. He found Jones’s golden retriever, Shagg, unattended on the property. There was no sign of forcible entry to the cottage. A search of the premises soon revealed Thomas Hoyt Jones, Jr.'s naked body in the bathroom. He had been strangled.

Investigators on Kelley’s Island soon learned that Jones had arrived on the island on the weekend to close the cottage for the winter. He was accompanied by Angelo Darnell Vaughn, identified later as Jones’ houseman, cook, and chauffeur. Vaughn was missing, as were Jones’ 1983 Dodge Aries station wagon, two televisions, his watch, ring, and two credit cards. Vaughn was last seen leaving Kelley’s Island that morning on the 9 a.m. ferry to Marblehead. He quickly became the chief suspect in Jones’ murder. A warrant was issued for his arrest.

Learning that he was the subject of an intense search, Vaughn telephoned Cleveland police on November 11, 1984, to arrange his surrender. He was arrested inside Jones’ station wagon at the Brookpark Rapid Transit station parking lot. In Vaughn’s possession was Jones’ watch. The watch was easily recognizable since its face bore the initials THOMAS H JONES in place of numerals.

While in custody, Vaughn admitted that he had placed Jones in a chokehold and held him for 8 to 10 minutes. At trial, Vaughn asserted that he had acted in self-defense. He testified that Jones had attacked him in the cottage's bedroom and that he was defending himself. At the time of his death, Jones was 70 years old. Vaughn was 19. Vaughn’s defense did not explain the bruising on Jones’ face, the fact that the body was subsequently dragged from the bedroom into the bathroom, or the theft of Jones’ vehicle and possessions. A jury of eight men and four women convicted Vaughn of first-degree murder. Vaughn was sentenced to 15 years to life for Jones’ murder, plus an additional two years for stealing Jones’ car.

Vaughn served 20 years in prison for Jones’ murder. After his release from prison, Vaughn was befriended by and allowed to reside with an acquaintance in the Slavic Village area of Cleveland. Within a week, Vaughn attacked the acquaintance with a hammer while sleeping and took $400 and his car. While the victim survived, his injuries were extensive and permanently disabling. He spent 28 days in intensive care and wore a helmet to court covering a hole the size of a pop-can top in his skull. At trial, he testified that he hoped to walk again someday. In 2007, Vaughn received a 40-year prison term for the attack.

The long-term legacy of Thomas Hoyt Jones Jr. is not diminished by the tragic events on Kelley’s Island in November 1984. The land donated by Thomas and Brooks Jones to the Cleveland Museum of Natural History remains today a vital stopover for migratory birds crossing Lake Erie, allowing birds time to rest and find nourishment before continuing their annual flight south. The site has become a key research area for the study of bird habitats and migration. In 2006, Long Point was renamed to the Jones Preserve in memory of the two brothers.