Places

Historical Places

Glenville Race Track

Because of interest in developing trotting races, the Cleveland Driving Park Company built a racecourse in 1870 in co-operation with the Northern Ohio Fair Association. Stockholders included Warren Corning and Howard Hanna Sr. The track located on St. Clair Avenue between East 88th and East 101st streets, was part of an 87-acre development that attracted the city's wealthy sportsmen in the summer. A bridge over St. Clair connected the track with the fairgrounds.

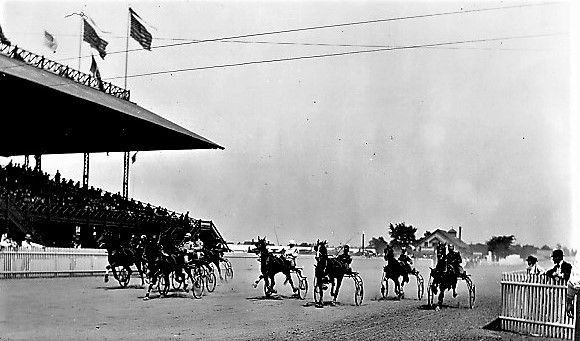

The Glenville Race Track remained successful after the fair closed with harness racing the principal attraction. Fast horses and their colorful owners, trainers, and drivers proved to be a more enduring draw.

The Cleveland Driving Park Company considered the first amateur driving club in America, featured foot, bicycle, horse, and harness races and attracted wealthy horse enthusiasts such as William Bingham, Liberty Holden, and Samuel Mather.

The Glenville Race Track joined with Buffalo, Rochester, and Utica, New York in 1872, to become the Quadrilateral Circuit. Within the year, the group became part of the Grand Circuit, the major league of harness racing.

In 1885, the track claimed the national trotting record for the one-mile, set by Maud S., a horse owned by William Vanderbilt, at the blistering speed of two minutes, eight and three-fourths seconds. After that, Maud S.s golden horseshoe hung at the entrance to the track, and lithographs of her likeness adorned stables throughout the country.

The idea of adding amateur competitions to the track’s offering was hatched in 1895 on the veranda of the nearby Roadside Club by a group of well-to-do horsemen. They subsequently styled themselves as the Gentlemen’s Driving Club of Cleveland. Club members gathered at the track every Saturday afternoon during the summer and early fall to compete in trotting races and four-in-hand contests. Gentlemen commanding the fastest trotters won cups.

The Boston Challenge Cup Race for trotters took place at the Glenville Race Track under the auspices of the Gentlemen’s Driving Club.

The four-in-hand horses pulled carriages called “tallyhos.” Each carriage had a footman who acted as a trumpeter, playing a very long brass horn. The lower part of the carriage was closed; the parallel seats high atop carrying the drivers. Those who drove their four-horse team with the most exceptional skill received blue ribbons.

A gentleman who won his amateurs treated his comrades to a lavish dinner, at which the loving cup, filled with an endless supply of champagne, was passed around. These celebrations took place in the trophy room of the horsemen’s “shacks,” stables usually built at or near the track.

One of the leading athletic events of the decade was the initial meeting of the Ohio Collegiate Athletic Association at the Glenville Race Track in 1902. Participants were Western Reserve University, Case School of Applied Science, Ohio State University, Oberlin College, Ohio Wesleyan University, and Kenyon College.

In 1903, as the age of the automobile dawned in Cleveland, crowds assembled at the Glenville Race Track, which had expanded its use for auto racing. Over ten thousand spectators witnessed the greatest automobile races held in America at the Glenville Race Track. The Winton Bullet shattered records, and the White Steamer broke the world’s track record for steam carriages

Barney Oldfield was the hero of the races, driving his Winton Bullet a mile in 1-½ minutes. As he finished, a left front tire exploded, but Oldfield held his car on the track. Two crashes overshadowed Oldfield’s performance. The Gray Wolf, a Packard automobile, went out of control, hit the fence and injured both car and driver. Both were sufficiently repaired to race again the next day.

In the last two races, Dan Chisholm of Cleveland drove a Baker Electric Torpedo five miles in less than 6-½ minutes. In the latter event, Chisholm lost control of the Baker Electric. He was able to stop the car, but several spectators were injured.

The sporting life of the Glenville Race Track continued to overflow into the nearby Roadside Club, where race spectators and participants wined and dined. Even after harness racing lost its appeal, the Roadside Club prospered as a gambling club.

Frederick Goff became mayor of Glenville in April 1903. As mayor, he succeeded in abolishing gambling at the Glenville Race Track, much to the dismay of influential friends. With betting illegal, the popularity of trotting races, the main attraction at the Glenville track waned, and the center of local racing shifted to the village of North Randall. The Gentlemen’s Driving Club passed out of existence before World War I.