People

Notable People

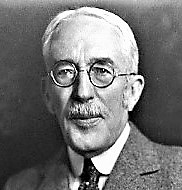

Samuel L Mather Jr. - Partner of Pickands Mather & Company

12023 Lake Shore Boulevard

Samuel Mather, industrialist and philanthropist, was a man of great inherited wealth who seemed to have a knack for accumulating even more wealth.

Samuel Livingston Mather Jr. was born in Cleveland on July 13, 1851, the first son of Samuel Livingston Mather Sr. and his first wife, Georgiana Woolson Mather. He was a descendent of James Fenimore Cooper on his mother’s side and Increase Mather, founder of Harvard University, on his father’s side.

His grandfather, Samuel Mather Jr., and Daniel Lathrop Coit were some of the first 49 stockholders in the Connecticut Land Company that surveyed the Western Reserve Lands in 1796. His father, Samuel Livingston Mather, came to Ohio in 1843, at the age of 26, to look after his father's landholdings. Four years later, he was one of the Cleveland Iron Mining Company founders that pioneered the iron ore trade in the 1850s.

Samuel was only two years old when his mother died of tuberculosis following the birth of his sister Katherine. Samuel was first educated at Miss Elizabeth Haydn’s private school on Lake Street (Lakeside Avenue). He continued in Cleveland Public Schools and St. Mark’s School in Southborough, Massachusetts.

Samuel was brought into his father's business while a teenager. Whenever his father noticed the slightest sign of weakness in his character, Samuel was readily disciplined. For example, Samuel's father gently but firmly convinced him to curtail an eighteen-month European tour because he was concerned about him being "away any longer from home influences." His father feared that his Catholic traveling companion was overpowering him with inappropriate influences.

The summer of 1869 changed Samuel's life. He was eighteen years old and worked as a timekeeper in his father's mines in Ishpeming, Michigan. Unfortunately, an explosion of black powder seriously injured him. His skull, spine, and arms were fractured. His lengthy recovery prevented him from entering Harvard, and he retained a permanently impaired left arm.

Following his injury, Mather was away on an eighteen-month European tour from 1872 to 1873. His father had encouraged him to stay another year until he had fully regained his health. However, he reminded Samuel, “We shall be very lonely without you.”

Mather's father believed that social connections were necessary to establish one's foothold in the world. Thus, he expressed despair when Samuel, while traveling in Paris, failed to deliver the letters of introduction he had written on his son's behalf. Samuel agreed and preceded his subsequent trips to Europe and the Far East by carrying letters of introduction from well-placed individuals.

In 1883, Samuel joined Jay C. Morse and Colonel James Pickands in a partnership to deal in pig iron and coal to compete with Mather’s father. Under senior partner Mather, the firm became a sales agent in new iron ranges in Wisconsin and Minnesota during the 1880s and 1890s. To facilitate its business, Pickands Mather began to manage Great Lakes docks. In 1913, the firm organized its vessel companies into the Interlake Steamship Company, the second-largest fleet operating on the Great Lakes with thirty-nine carriers.

After two years, the company leased a mine in the Gogebic Range, later acquiring interests in the Minnesota Mesabi and Michigan Marquette Ranges. Mather allied Pickands-Mather with the steel industry, providing resources and transportation and facilitating the U.S. Steel merger in 1902.

Pickands, Mather & Co. became one of the four major iron ore companies in the United States. The business grew until the 1940s and included iron-ore mines on all the Lake Superior ranges, mining and distributing coke, and managing the Interlake Steamship Company fleet with 36 freighters transporting iron ore, coal, and limestone, and grain on the Great Lakes. Shoreby, Mather's home located at 12023 Lake Shore Boulevard, offered an excellent view of Cleveland's port so Mather could observe which of the iron-ore boats steaming toward the city belonged to Pickands Mather.

In addition to mining operations in the Lake Superior district, the company was also engaged in developing processes for the benefit of low-grade iron formations. This material, called taconite, existed in large quantities in the Lake Superior district and was looked upon as a significant source of the future supply of iron-bearing material.

In the 1890s, Mather was a leader in the move for increased participation in community affairs. After returning from travels in England and Europe, he confessed that for the previous twenty years, he had grown "less attentive to his duties as a citizen, until he came to neglect them well-nigh all together." He declared that no one was to blame for corrupt bossism in city government but those who allowed the bosses and ward politicians to gain complete control.

Mather followed up his exhortations with actions. He was on the first executive committee of the Municipal Association, was active on a commission to create a group plan for public buildings, and tackled problems of public sanitation by promoting a municipal garbage reduction plant and an adequate water supply tunnel for the city.

He was a director of United States Steel Corporation, Cleveland Cliffs Iron Company of West Virginia, Interlake Steamship Company, American Ship Building Company, and Union Commerce National Bank.

Samuel was an avid horseman and took great pleasure in an excellent swift tour. After one of these impulsive outings, Mather felt re-invigorated. "I took a long drive yesterday afternoon and feel better today." But the love for the horse gave way to the motorized vehicle when it appeared on the scene in the 1890s. Mather, along with other affluent families, acquired the latest automobile models for their use and play.

Mather was senior warden and vestrymen of Trinity Cathedral, president of Federated Churches of Greater Cleveland, and a trustee and benefactor of Hiram House. During World War I, he organized the War Chest and received the Cross of the Legion of Honor from the French government. In 1919, he helped establish the Community Chest, contributing annually, and in 1930 established a trust fund to ensure its prosperity.

Samuel grew up in his parent's home at 1369 Euclid Avenue, just three houses from Flora Amelia Stone at 1255 Euclid Avenue. Their relationship developed, and they married on October 19, 1881. Flora was born on April 8, 1852, the youngest daughter of Amasa Stone, who made a fortune in bridge building, railroads, and banking.

Following a European honeymoon, they lived with her parents. Samuel and Flora had four children: Samuel Livingston III, born on August 22, 1882; Amasa Stone, born on August 20, 1884; Constance Mather (Bishop), born on September 21, 1889; and Philip Richard, born on May 19, 1894.

Flora Stone Mather, a devout Presbyterian, was devoted to Old Stone Church. She dedicated her career to aiding the sick and impoverished. Her parents instilled gratitude for her comfortable life and a deep sense of responsibility for those of lesser means. Flora was ambitious in her lifelong effort to enhance the lives of sick, impoverished, and homeless Clevelanders. Her work was similar to that later assumed by the city's Visiting Nurses Association, created in 1901 under the auspices of Goodrich House, Alta House, and Hiram House, all of which she was a founder and benefactor.

Flora was also vitally involved in the civic life of the community. She planned and supported Goodrich House, the center of the social settlement movement in Cleveland. It was here that many of Cleveland's future leaders came to live as residents among the immigrants who labored in the nearby steel mills. Mrs. Mather started the Consumers League of Ohio, using Goodrich House as its base. The League's investigations of sweatshop conditions led to the clean-up of filthy bakeshops and candy factories. In addition, they prepared the way to abolish child labor in Cleveland.

The Mathers were active in the national area and had many of the country's leaders in politics, commerce, and culture as their companions. Flora accompanied her brother-in-law, then secretary of state, to a private dinner party at the White House in 1905, hosted by President and Mrs. Teddy Roosevelt. She had expected a "dreadfully dull" evening. Still, to her pleasant surprise, it turned out to be quite an exciting affair.

Samuel decided in October 1909 not to move from Shoreby into a newly built house on Euclid Avenue because of Flora's health. Flora succumbed to breast cancer on January 19, 1909. The majority of her estate endowed the missions of Children's Aid Society, the Presbyterian Society, The YMCA and YWCA, the Goodrich Social Settlement, and the Cleveland Day Nursery. Samuel never remarried.

On September 16, 1931, Mather's fifteen-year-old grandson, Samuel Livingston Mather IV, being despondent over the death of his mother, committed suicide at the family estate in Mentor, Ohio.

Ten days after his grandson's burial, Mather endured a particularly severe heart attack and died in his Shoreby home on October 18, 1931, at age eighty. His funeral was fit for a monarch. President Herbert Hoover, John D. Rockefeller, and General John J. Pershing paid their respects personally. He was buried in Lake View Cemetery alongside Flora.

When Samuel Mather died, he was the richest man in Ohio. His estate was divided among his children, grandchildren, and daughter-in-law, and various charitable causes. Primary beneficiaries of his financial largesse were Western Reserve University, John Carroll University, Kenyon College, University Hospitals of Cleveland, the Episcopal Church, St. Luke’s Hospital in Tokyo, Japan, and the Community Chest. In addition, during the Great War (World War I), Samuel helped raise funds for the government and donated $750,000 of his own money to the war effort.

Because of declining stock values in the Depression, the bequests could not be paid. As the estate's value increased with market improvements, heirs contested the will, since Mather had changed the terms within a year of his death, and some bequests, notably one to Western Reserve University, were invalidated.